Someday your bones will be part of the bedrock…

Beaches, Limestone Quarries, Phosphate Mines & Florida

Category Archives: Florida Keys

Formation of the Florida Keys

Posted by on October 20, 2011

The Florida Keys are a chain of limestone islands that extend from the southern tip of the Florida mainland southwest to the Dry Tortugas, a distance of approximately 220 miles. They are island remnants of ancient coral reefs (Upper Keys) and sand bars (Lower Keys) that flourished during a period of higher sea levels approximately 125,000 years ago (a period of geologic time known as the Pleistocene Epoch).

During the last ice age (100,000 years ago) sea level dropped, exposing the ancient coral reefs and sand bars which became fossilized over time to form the rock that makes up the island chain today. The two dominate rock formations in the Keys are Key Largo Limestone and Miami Oolite.

During this time of lower sea levels, the Florida land mass was much larger than it is today and the area now referred to as Florida Bay was forested. As glaciers and polar ice caps started melting 15,000 years ago, flooding of land combined with tidal influence changed the geography of the Keys and their surrounding areas.

The Upper, middle and lower keys are categorized based on their geology. Because the upper keys were higher and generally longer than the lower keys, there were fewer channels for water to flow and impede coral growth, that is the reason there are more and shallower outer reefs in the upper keys. This effect can easily be seen on a map. The flow was so significant that the lower keys are aligned more north and south than the upper keys. It was so killing that very little coral has grown west of Key West in the last 6000 years.

The Upper Keys begin with the Ragged Keys of Biscayne National Park to the north and run to Lower Matecumbe to the southwest.

The Middle Keys include the islands south and west of Lower Matecumbe to Marathon (Seven Mile Bridge).

The Lower Keys include Big Pine Key through Key West.

Today, sea level continues to rise in the Florida Keys. The measured rise at Key West has been almost 30 cm since 1850 (Maul and Martin, 1993)

To read more about the cultural history of the area check out www.keywesthistory.org

Information obtained from: Geology and Hydrology of the Florida Keys, U.S. Geological Survey

Windley Key Fossil Reef ~ Friday, October 8

Posted by on October 16, 2011

The first location we visited was the Windley Key Fossil Reef Geological State Park located in Islamadora, FL. This site is an old limestone quarry that was active during the early 1900’s for railbed material until 1912, then into the 1960’s as a supply of keystone. Over a decade ago, the Florida Park Dept. designated it as a geological site. It now serves as an excellent example of key largo limestone and provides easily accessible, dry land views into the ancient coral reef that formed the Keys.

Windley Key State Park includes approximately 30 acres of significant botanical, geological, and historic resources. I was extremely impressed with the entrance building which turned out to be a museum quaintly named the Alison Fahrer Environmental Education Center, far from the all-too-common chincy tourist welcoming station. Shortly after walking in I learned the nifty fact that it’s the tallest island, Windley Key boasts a towering highpoint of 18 feet above sea level.

The fossilized coral of this coral reef is known as “key largo” limestone, defining the surface rock of the Upper and Middle Keys, from Sand Key to Loggerhead Key. Approximately 100-125 thousand years ago, during the pleistocene period, the Keys’ landmass was underwater and the reef corals thrived. During the last interglacial ice age water began to recede as it became part of the polar ice caps. This lowered the sea level to expose the reef, ultimately leading to the reef’s demise and the formation of the islands of the Florida Keys.

The 8' Cross Sections allow us to explore the massive reef corals as they were first deposited. In situ coral colonies and reef rubble make up most of the limestone. Star Coral is identified in the upper right area of this section. Fossils of many varieties of coral can be seen in these rocks. As modern biology informs us, each kind of coral tells a specific story about geologic setting. A sedimentary geologist must interpret these fossils to tell the story of the rocks.

The main structure that formed the Key Largo limestone is a network of massive coral heads with spaces filled by reef rubble. The dominant species found in the limestone are Star Corals and Brain Corals. Both species are common in patch reefs, making this Pliestocene aged fossil reef at Windley Key comparable to the modern reef tract that exist today. However, there seems to be some debate as to how the similiarities between the reefal environments can be used in a scientifically. I’ve read some conflicting opinions but overall, the general idea that Key Largo limestone formation can provide insight is noteworthy. One of the articles is an interesting Coral Reef Report based on the steady demise of coral species, Acropora spp. in the Atlantic ocean.

The Key Largo Limestone is a white to light gray, moderately to well indurated, fossiliferous, coralline limestone composed of colonial coral heads in a calcarenitic matrix. Little to no siliciclastic sediment is found in these limestones.

The fossil below appears to be Brain Coral, note the curvy impressions of the fossil.

Windley Key Fossil Reef Visitor’s Center ~ Saturday, October 8

Posted by on October 15, 2011

Alison Fahrer Environmental Education Center

There is much to be appreciated in the preserved remains of the “ancient reef forest” (abandoned limestone quarry) at Windley Key State Park. The fossilized coral is the star of the show but the Visitor’s Center is a highly recommended prelude to the Quarry.

The Alison Fahrer Environmental Education Center provides an impressive introduction before entering the site. It features exhibits about the area’s history, geology and biology. Windley Key Quarry is one of only two State Geological Sites in Florida and the only place on earth where one can walk through an in-situ coral reef. The quarried Key Largo limestone was even used to build the education center. Sawn blocks of the polished coralline limestone, known as “keystone” (a decorative building material), construct the walls of the center.

One of the main attractions of the museum is a “hands-on” model constructed of the quarry limestone. The model depicts the geologic evolution of the reefal Limestone that forms the upper and middle Florida Keys and is the counterpart to the modern offshore reef tract.

Described in classic studies by Dr. John Edward Hoffmeister (University of Miami), the 125-ka reef extends for more than 175 km along the Florida shelf, is up to 55 m thick, and underlies the offshore living reefs. (USGS)

View of Quarry and Overseas Railroad exhibits in Education Center (image courtesy of floridastatespark.com)

Henry Flagler, who built the Overseas Railway that once connected the Florida Keys, first mined the Key Largo Limestone at Windley Key and adjacent quarries in the early 1900s. The rock was used for commercial construction purposes and decorative facing stone. Mining ceased in the early 1960s. It was near the Windley Key quarry that the Flagler Station was located. Use of the railroad ended in 1935 when a Category 5 storm swept the train from the tracks, killing more than 400 people.

Big Pine Key “Blue Hole” ~ Saturday, October 8

Posted by on October 14, 2011

After spending the morning in Windley Keys, we left the Upper Keys region and headed south to the “Blue Hole” of Big Pine Key in the Lower Keys. Blue Hole is an old limestone quarry but unlike Windley Key, it filled with water after the rock was exploited. The limestone was used to build many of the original roads in Big Pine Keyin the 1930’s and 1940’s. Oddly, to this day it is unknown who dug it. The bottom of the Blue Hole filles with saltwater from surrounding marine areas filtering in through the underlying porous reef rock (Key Largo limestone). Above the saltwater is a freshwater habitat; the freshwater is lighter than the saltwater so it floats on top, forming a lens. Scattered rainfall and a saturated bed of compacted oolitic sediment (Miami limestone) overlying the ancient coral reef keeps the freshwater habitat replenished even in times of drought.

The largest and best known of the surface freshwater ponds on Big Pine Key is Blue Hole. (Photo courtesy of Aurther Wistenly)

Freshwater is very important in an island ecosystem and the Blue Hole provides this vital resource to many animals, including the Key deer, American alligator, turtles, and various species of birds. There are many different types of fish that populate the lake, both saltwater and freshwater species. I saw a few fish and spotted a turtle basking in the sun. Unfortunately I never caught sight of an alligator or one of the infamous deer, though I admit I didn’t look very hard. It wasn’t the fauna around Blue Hole we came to study, it was geology. The main attraction was the sediment beneath our feet…oolite! Big Pine Key & Lower Keys are formed by deposits of oolitic limestone, known as Miami limestone, while the Upper Keys consist of Key Largo limestone. The oolitic rocks make up a facies of the Miami limestone which rests above the Key Largo Formation. Aside from composition a major difference is that oolitic limestone can hold fresh water.

Oolite from the Miami limestone, surface layer above the Key Largo Formation. Notice the small nodules, called ooids, they are the grains that compose the oolitic limestone of the lower keys.

The Florida Keys lay on a thick bed of limestone. Key Largo Limestone is the surface rock of the Upper Keys and the miami limestone covers the lower keys. Contact between these rock formations found at Big Pine Key show that the oolitic miami limestone overlaps Key Largo limestone (USGS).

Check out this nifty panoramic view of Blue Hole

Veterans Beach ~ Saturday, October 8

Posted by on October 13, 2011

Our visit to Veterans Beach gave us the opportunity to observe some key plant species in the shallow waters near the shore. I also took some time to examine the beach sand. It appeared to be coarse, biogenic carbonate sand composed of coral and shell fragments and a lot of dark colored grains with carbonate mud which made it somewhat clumpy to the touch. Overall, the sand of Veterans beach is composed more of coral and mollusk shell fragments than of quartz crystals. It’s very different from the beaches around the Tampa Bay area, where sand is usually of fine, white quartz crystals.

The floor is covered in sea grasses, penecilis, halimaeda and a little udatea. I collected three different samples, as you will see in the photo further below. The squishy mud on the beach bottom felt strange but definitely a great opportunity to observe part of the carbonate cycle. I had a chance to see the life and death stages of Halimeda: while alive, growing in the ocean sediments and dead, littering the beach as dried, calcareous flakes. Florida sands are formed from fragmented skeletal remains of organisms. Some are from calcareous algae,

others from the calcium carbonate skeleton or coral. Wave action from

storms and hurricanes redistributes these sediments locally

The grasses that grow near the shore are continuously pushed up from the roots and then shed. As a result they are actively replaced all the time. Of course, both components of the system – the grass and the calcified algae on them – depend on sunlight for their growth. They thrive in these shallow waters, protected from the turmoil of the open ocean, and they form enormous amounts of mud in a very short time.(Life as a Geological Force (1991) – Peter Westbrook)

Anne’s Beach ~ Saturday, October 8

Posted by on October 12, 2011

This photo demonstrates the lack of wave action owing to its extreme shallowness, typical for Florida Key beaches. Unlike the beach sediment at Veterans Beach, here you'll find very fine carbonate mud

Foot in the carbonate mud, produced by the release of fine carbonate material from the breakdown of calcareous algae, such as Halimeda.

After pilfering algae from Veterans Beach we continued to Anne’s Beach, located in Lower Matucumbe, part of the middle Keys. This natural, narrow beach is nestled with mangroves and surrounded by a wide expanse of calm, shallow water. Most importantly it

This beach, in particular, is often mentioned as a “must see” hidden gem in the Keys. I couldn’t agree more. It’s length makes up for the small width and there’s plenty of shoreline to saunter past, including a boardwalk. It was the perfect place to wind down after our busy day.

It was a great place to observe carbonate mud formations; the area is covered with squishy lime mud. I managed to find lithified and partially-lithified pieces of mud and noticed very few corals or shells. It’s an unusual beach because the sandbar is composed entirely of lime mud (aragonite & calcite). Most beaches, nearly everywhere are dominated by quartz. Quartz does not break down easily and therefore tends to be the most abundant beach sediment. Whereas calcium carbonate erodes and dissolves easily, by all means of chemical, biological and physical weathering. It’s far less likely to stick around the way that quartz does.

I proudly present a sample of lithified micrite (left) & partially lithified mud (right). Professor Onac found the lithified specimen. Anne's Beach provided a modern mud bank & the opportunity to observe 3 stages of Carbonate mud; post deposition/formation(lime mud), partial lithification & lithification.

360 degree view of Anne’s Beach

360 degree view from the boardwalk of Anne’s Beach at Mile Marker 73.

John Pennekamp Coral Reef ~ Sunday, October 9

Posted by on October 11, 2011

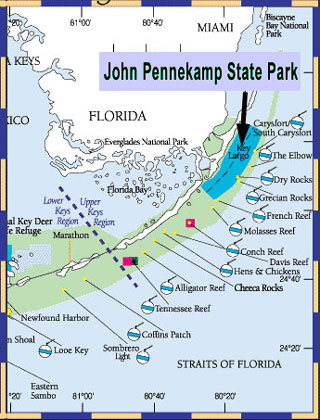

The John Pennekamp Coral Reef State Park includes approximately 3,169 acres of upland and 53,860 acres of submerged lands on North Key Largo. It’s the 3rd largest barrier reef in the world and the only barrier reef in North America.

On Sunday we went snorkeling in two locations at the park. The first snorkel location was around 40 feet deep and the second was deeper, more like 80 feet deep. Both hard and soft corals were abundant including a large number of sea fans. There were many schools of fish swarming about. I spotted a ray swimming quickly by – I couldn’t tell whether or not it was a spotted ray. The visibility was excellent at both spots.